L.A. Gastronomical

JKG Odéon

Jean-Kenta Gauthier Odéon

5 rue de l'Ancienne-Comédie 75006 Paris

Opening: Wednesday 28 May, 5?8pm

Opening hours: Wed?Sat, 2?7 pm

"[...] sixteen hamburgers in two days. I got this incredible case of dysentery." — Robert Cumming, 2016

"I drove through the streets of LA, stopping at street food vendors. At each location I used one of the constellation dollars." —

David Horvitz, 2023

Jean-Kenta Gauthier is pleased to present L.A. Gastronomical, an exhibition of conceptual art created in Los Angeles, where Robert Cumming's fast food meets David Horvitz's street food, and where constellations enter circulation.

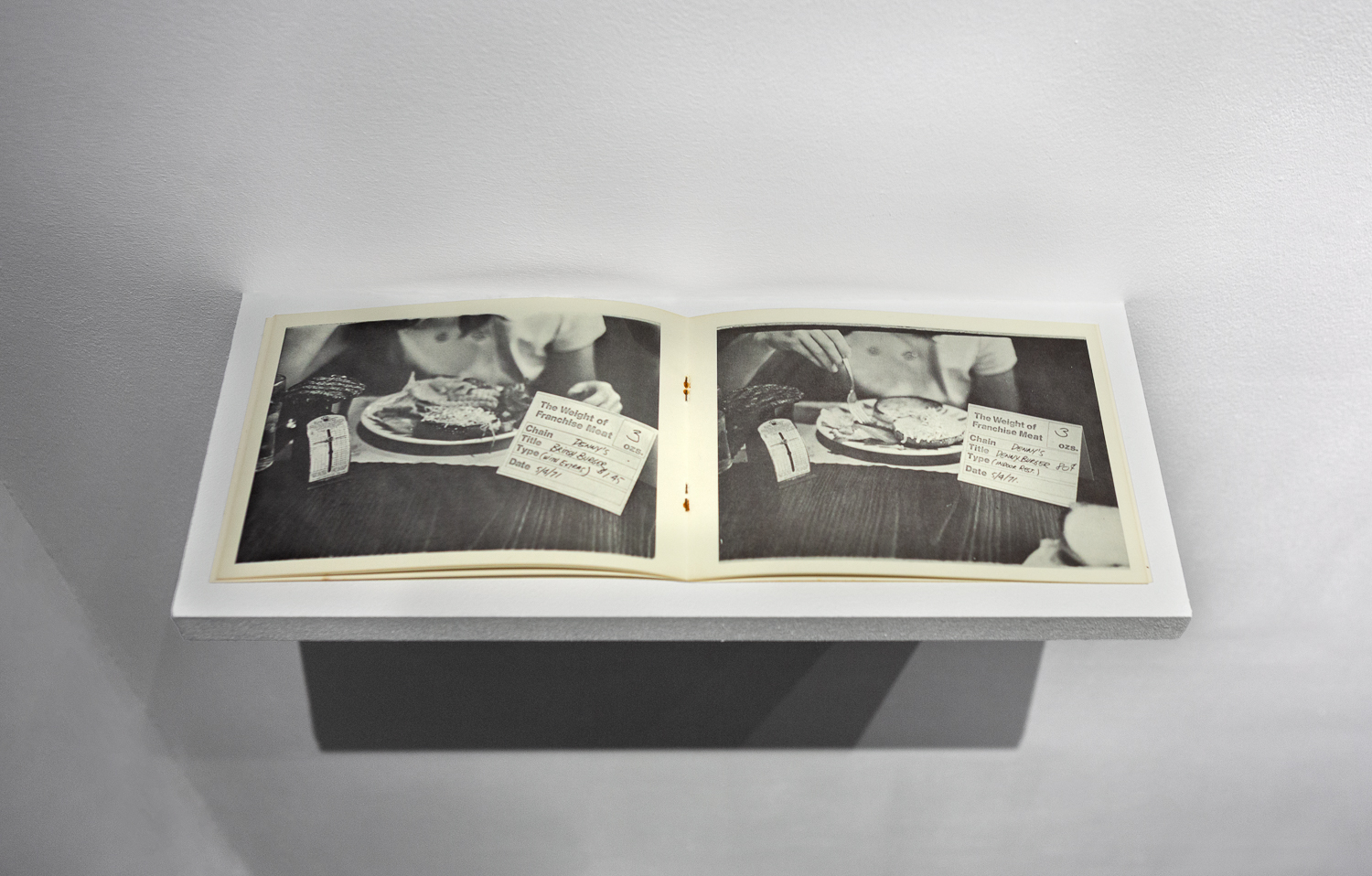

Robert Cumming, The Weight of Franchise Meat (1971)

Born on the East Coast of the United States, Robert Cumming (1943?2021) moved to the West Coast in 1970. "I was really thrilled about a lot of things about California," he recalled in a 1978 interview with critic James Alinder. That same year, Cumming was already considering leaving California and returning East, which he would do two years later, having had his fill of the illusions offered by the region, its consumer society, and its film industry. He continued: "The hamburger was one of the things I wanted to spot-light."

On May 4 and 5, 1971, he set out to create a typology of hamburger patties from fast food restaurants in Los Angeles. Titled The Weight of Franchise Meat, these sixteen photographs made up his second artist's book self-published that same year, released in an edition of 500, and now among the rarest of his publications. In each photograph, two recurring elements appear: a small pre-printed card bearing the project title and fields to be filled in (weight, name of fast food chain, hamburger name—which Cumming considered the "title"—, type of order with price, and date), and a postage scale, a nod to Cumming's mail art practice from the 1960s before moving to California. In a 1994 letter to Frédéric Paul, then director of FRAC Limousin, Cumming wrote: "I saw the entire mail system as a working class exhibition; from the people at the post office to the people who sorted mail to the postman who delivered the work and finally the recipient." A social concern for art not far removed from this study of low-cost dining, which takes the form of a consumer survey.

Cumming quickly became a key figure in the Californian conceptual art scene, gaining rapid success and joining a circle of close artist peers including AA Bronson, Robert Heinecken, Edward Ruscha, and William Wegman, under the mentorship of Douglas Huebler, a pioneer of conceptual art who had introduced Cumming to conceptual photography in 1969. That same year, Cumming participated in the landmark Art By Telephone exhibition at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago. In 1971, alongside artists such as Michael Asher, Vija Celmins, Mary Corse, Jack Goldstein, Allan McCollum, Allen Ruppersberg, and William Wegman, he was selected for the group show 24 Young Los Angeles Artists, curated by Jane Livingstone and Maurice Tuchman at LACMA. There, he presented The Weight of Franchise Meat: the sixteen black-and-white photographs that comprise the book were mounted on board and adhered directly to the wall.

However, Cumming regarded the project lightly, believing it to be slapdash compared to his other photographic works, which often required weeks or months of preparation. In 1978, he told Alinder: "Franchise Meat was the result of acting prematurely on a very obvious idea. [...] It's too Californian and a little too easy. I did it right after I arrived in Los Angeles." And again in 2016 to critic David Campany: "The Weight of Franchise Meat, I really hate it. I went too fast with a bad idea." And yet, the project bears all the marks of Cumming's characteristic rigor of the absurd. It acts as a neutral inventory of everyday banality in American society—one could think of Twentysix Gasoline Stations (1963) by Edward Ruscha—and its somewhat improvised nature highlights a playfulness that is appreciated in certain strands of Californian conceptual art. "There was something about European conceptualism that seemed a little too dry for its own good. Maybe there was something about sunshine that kept people humorous!" noted Campany in the aforementioned interview. Cumming laughed: "The sunshine is supposed to melt your brains."

The Weight of Franchise Meat remained shelved for a long time: too Californian for an artist who would ultimately leave the West Coast (though he returned in 2015, this time to the desert, where he stayed until his death in 2021). It is not surprising that Cumming ended up setting aside his early Los Angeles projects, created when he was still—too?—under the spell of California and its mythos. The entire series was miraculously rediscovered in an archive box in early 2025. The twelve photographs presented in L.A. Gastronomical are precisely those exhibited at LACMA in 1971. Displayed on the wall just as in their original presentation, they attest to a time when, half a century ago, some artists in California took humor seriously. That same year, another Californian artist—with whom Cumming would later exchange works—had his students copy the line: "I will not make any more boring art."

David Horvitz, Constellatory Insertions Into Angelic Orbits (2023)

Half a century later, David Horvitz, an artist born in Los Angeles in 1981, carries this spirit forward. In the meantime, the city has expanded beyond measure. "In the City of Angels, the stars are hidden out of view above a blanket of light pollution," writes Horvitz, who has previously produced works addressing the issue of urban light pollution—for example, his phrase "Give Us Back Our Stars", displayed as prints or tapestry (2021). In Paris, he pursued this quest by turning off public streetlights to recreate a constellation through absence (Eridanus, 2017, shown at Galerie Allen, collection of Fonds d'art contemporain de la ville de Paris).

Created in 2023, Constellatory Insertions Into Angelic Orbits is a two-stage work. Recognized by the International Astronomical Union (founded in Paris in 1919), eighty-eight constellations populate the starry sky that eludes us in major cities; among them, forty-two represent animals: the dolphin (Delphinus), the swan (Cygnus), the lion (Leo), the fox (Vulpecula), the crane (Grus)... "Hidden somewhere in a cosmological landscape, in forests of light no longer visible, these animals are hiding," writes Horvitz. "I hole punched these animal shapes one-by-one into forty-two one-dollar bills. They are small drawings that become visible when held to a light source." This intervention on currency forms the first stage.

In 1970, under Brazil's military dictatorship, Cildo Meireles (born 1948 in Rio de Janeiro) created his Insertions into Ideological Circuits by stamping banknotes with subversive messages and releasing them into circulation. Constellatory Insertions Into Angelic Orbits draws its title from Meireles' historical project, while situating it within the context of the City of Angels. Horvitz's work enters its second stage through circulation. "I drove through the streets of LA, sometimes at night and sometimes in the day, stopping at street food vendors. They were mostly taco trucks and taco stands. [...] At each location I used one of the constellation dollars and purchased something. I wanted to put the dollars into circulation to be passed from hand to hand."

In the gallery, the photographs of the food purchased are displayed on the reverse of each bill's photograph—like constellations buried in an overlit night. As part of a project that is both performative and participatory, visitors are invited to gently turn over the works. The surprise of discovering the proof of the bill's circulation mirrors the moment when someone attentively lifts such a bill to the sky to check its authenticity and discovers, in negative, a constellation—by day or by night. "In the city of Angels, where are the stars?"

L.A. Gastronomical

With a clear sense of humor and five decades apart, Robert Cumming and David Horvitz insert Los Angeles' cuisine into their conceptual practices, documented through photography. Gastronomy is often measured by stars, and photography—an art of attention—teaches us to find astronomy within gastronomy.