Futur antérieur

Jean-Kenta Gauthier | Odéon

Jean-Kenta Gauthier Odéon

5, rue de l'Ancienne-Comédie 75006 Paris

Opening reception: Saturday 29 October, 5 - 8 pm

Opening hours: Wed - Sat, 2pm - 7pm

The exhibition Past Future presents a group of recent works resulting from the research and reflections undertaken by Hanako Murakami (born in Tokyo in 1984, lives and works in Paris) on the conditions of the advent and existence of photography. An archaeological undertaking of the medium, this vast project invites everyone to question both what photography is and what it could have been, and thus to question our desire to see and re-experience the world.

“At the beginning of a new season, I stood in Niépce's garden with my camera called Retina, hoping to capture what did not get into the square image he produced on that summer day, 200 years ago, at the birthplace of what was not yet called photography.” If Le Gras, in Saint-Loup de Varennes in Burgundy, is the house in which the inventor Nicéphore Niépce (1765-1833) created, on 26 June 1827, the View from the Window at Le Gras, the oldest photograph known to date, Hanako Murakami reminds us that the context of the birth of photography already lies in the nature that surrounded the house of its inventor. The first work to be seen from outside the gallery, Niépce’s Garden (2022) consists of a curtain on which a photograph of the trees surrounding Le Gras is printed. The work is to be placed in front of a window, so that each window becomes a metaphor for the point of view of the first photograph, and the image of the rays of sun invites the light of the world to enter the exhibition.

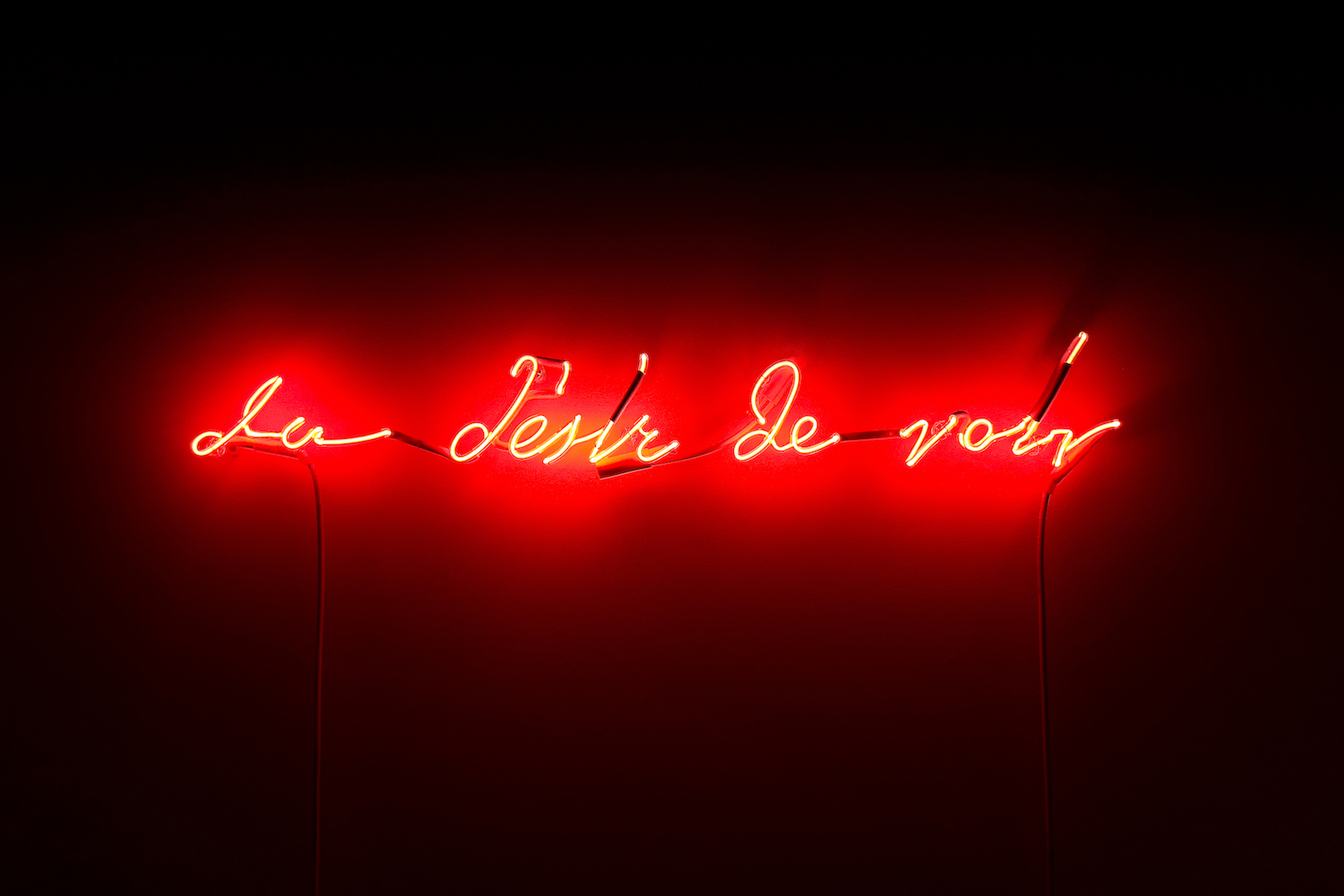

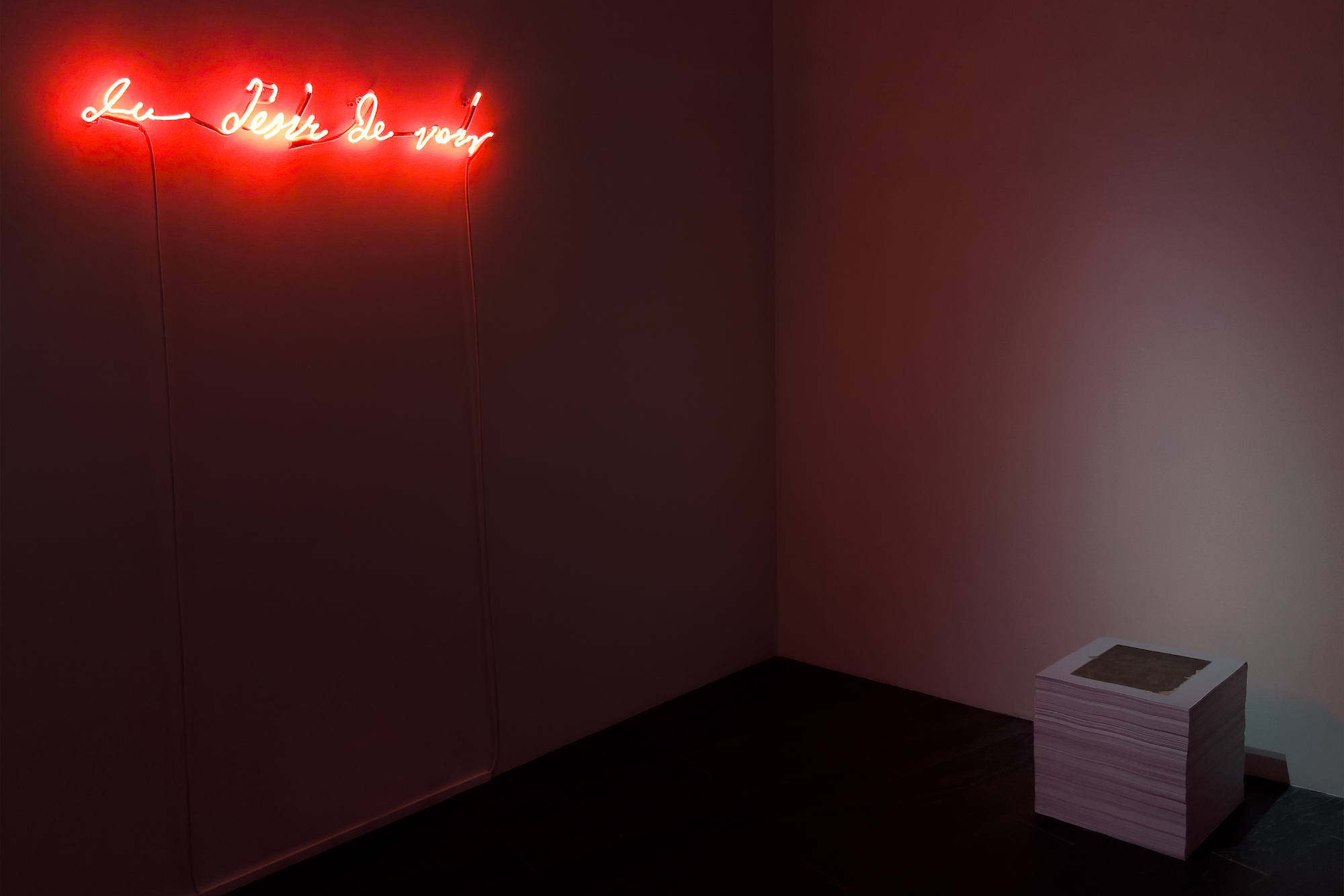

If the multiple developments of photography lead our societies today to be inundated with images, it is because it is a question of our will to know and our desire to see. A possible metaphor for a world which, by dint of wanting to see, even ends up surveilling, the large red neon sign with its handwritten letters has its origins in a quote. On February 3, 1828, the artist and entrepreneur Louis Daguerre wrote to Nicéphore Niépce about his latest discoveries and acknowledged to the latter that his discoveries seemed much more promising; he then concluded his letter with these words: “I cannot conceal from you that I am burning with desire to see your essays from nature” [Je ne puis vous dissimuler que je brûle du désir de voir vos essais d’après nature] . With Louis Daguerre to Nicéphore Niépce, 3 February 1828 (2022), Hanako Murakami inflames Daguerre's words while offering them an autonomy that seems both to recall the reasons for what at the time was not yet called photography, the yearning to be able to see and re-experience the world, and to indicate what, two centuries later, still seems to obsess our society.

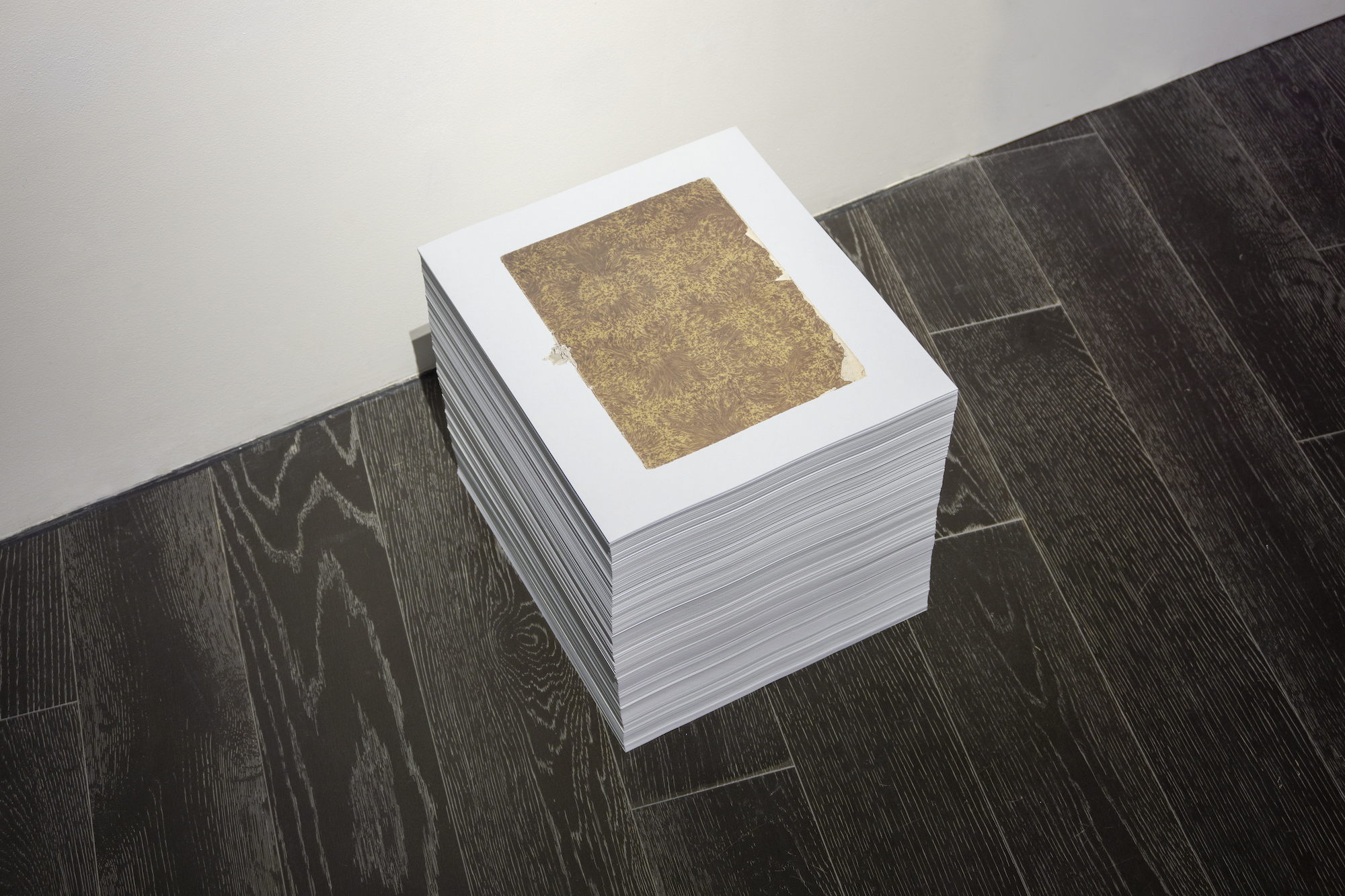

In 1829, Nicéphore Niépce wrote by hand a small treatise entitled Notes on Heliography [Notice sur l’héliographie]. If Hanako Murakami had already recalled in her work Nomenclature (2019) that in the years 1820-1830, twenty-seven words or groups of words were potential candidates to designate what would later be called photography, Nicéphore Niépce had concentrated most of his efforts on the realization of heliography or "writing of the sun", the first photographic process, a technique of fixing an image on a support. The treatise consists of eleven pages bound in a marbled cover. The stack of prints Invention (after Nicéphore Niépce, Notice sur l'héliographie, 1829) (2016/2022), recreated for the exhibition, refers to this manuscript. By reproducing on both sides of the paper an image of the cover and the back cover of this booklet, Hanako Murakami makes the treatise on the invention of the first photographic process fit into the thickness of a single sheet of paper, reminding us through its erasure that the history of photography is full of absences, like Niépce's 132 other experiments, of which little tangible evidence remains except for a set of notes - the subject of the work The Boxes (2019) presented at the gallery a year ago in the group exhibition Niépce: The Origin of the World and which today is part of the collections of the Musée Nicéphore Niépce in Chalon-sur-Saône. The prints, placed on the floor of the gallery, are offered freely to visitors, like photography, an invention acquired in 1839 by France, which, in the words of Louis Arago in his speech to the Academies of Science and Fine Arts, “was proud to be able to freely provide the whole world with it.”

Niépce's heliography, for the development of the image, required the combination of two ingredients, lavender oil and turpentine. On entering the gallery, visitors will have noticed the strong scent of Air de l’image [Air of the Image] (2022), an olfactory work recreated by Hanako Murakami by reproducing Niépce's mixture. If Niépce had spent a long time working on heliography, his entire studio and home were perfumed with the scent of a natural laboratory. The context of the beginnings of photography is also this smell which, filling the air of Le Gras, is like the scent of victory for the brilliant inventor. A work of Duchampian inspiration, Air de l'image is a quasi-readymade, like other works in the exhibition - and perhaps even all photography.

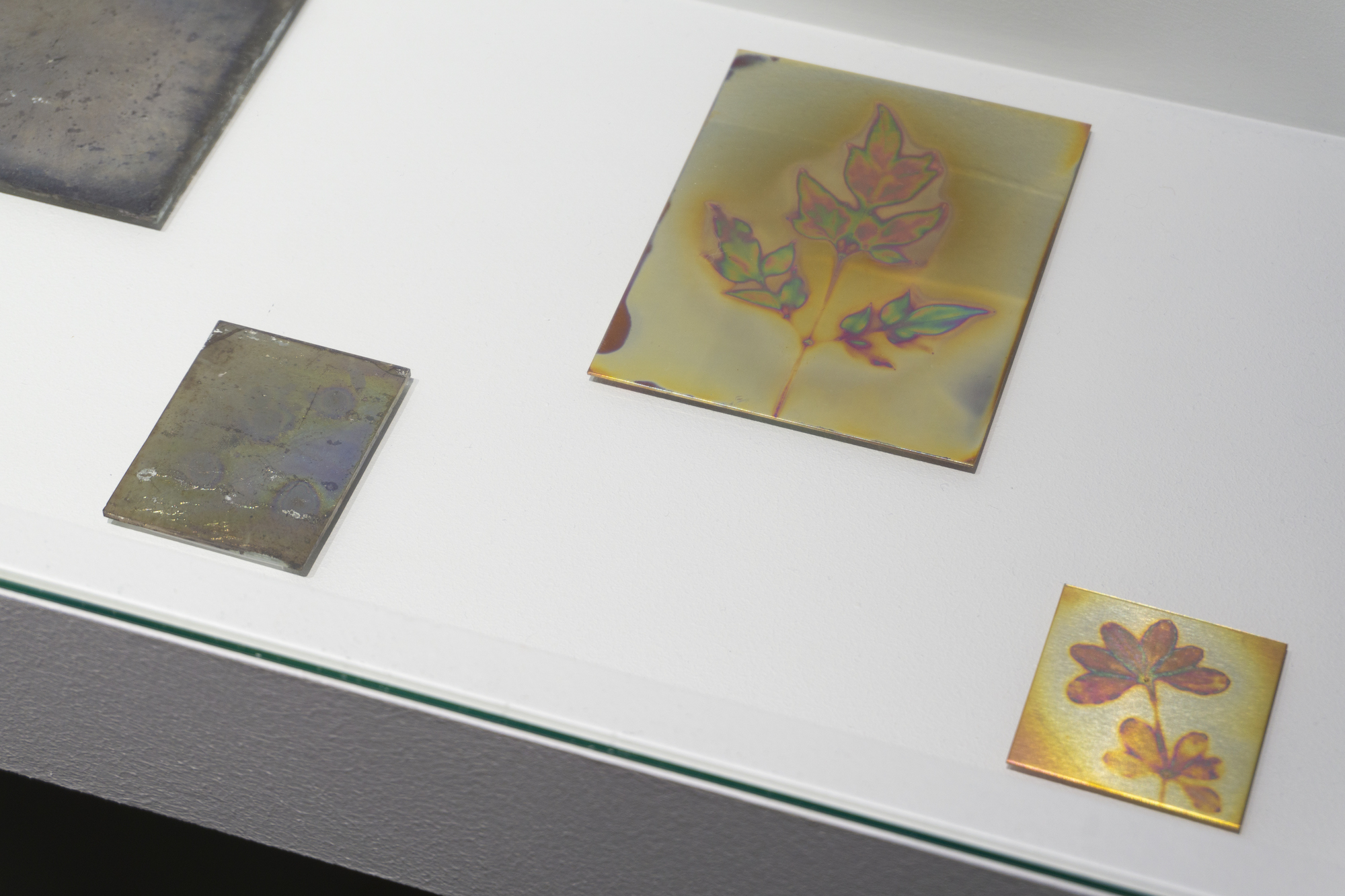

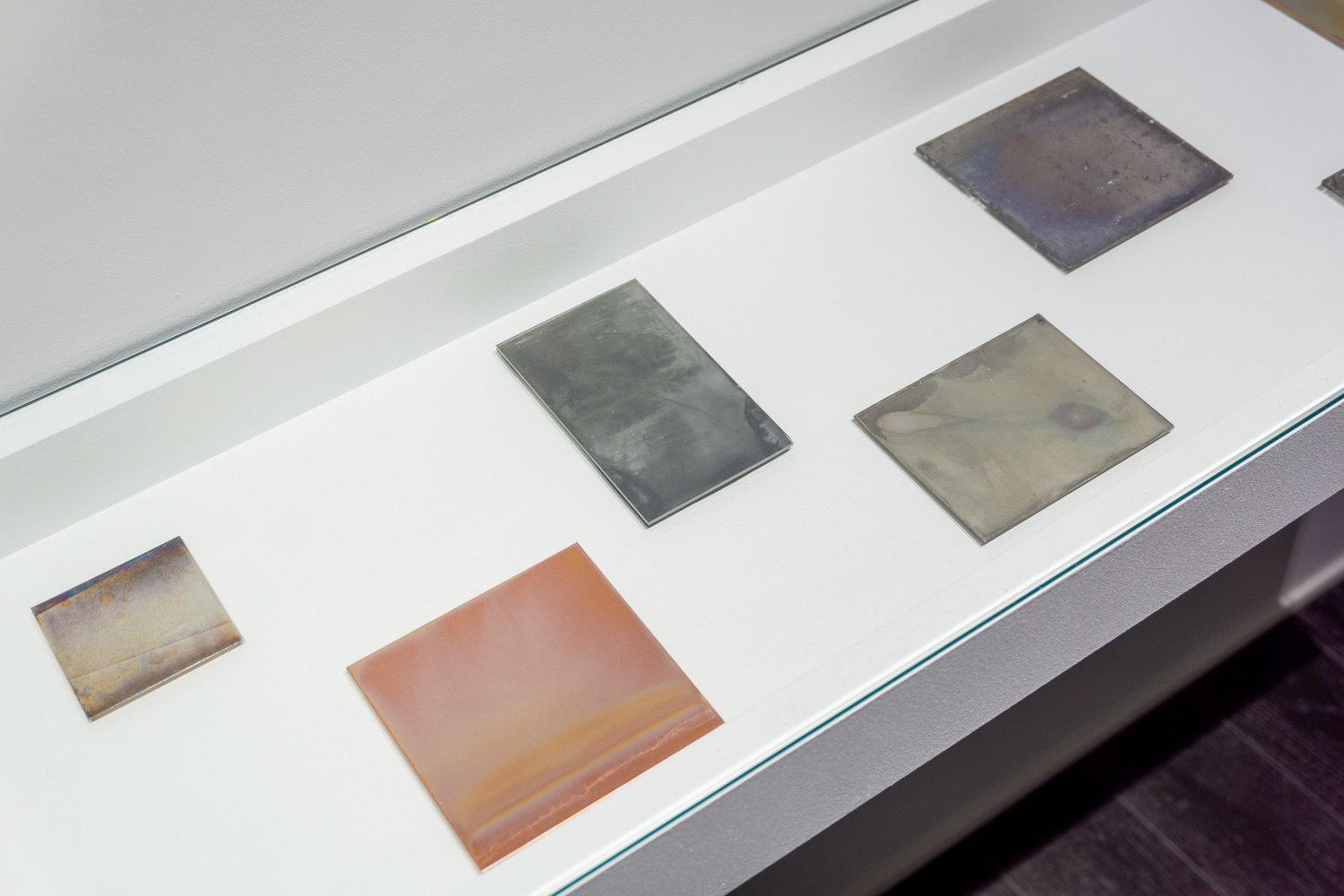

If Hanako Murakami is able to develop this vast archaeology of photography, it is because she has set about reproducing in minute detail each of the experiments conducted by Niépce, which he called "heliography", "physautotype", or "paratauphyse". The Field of Possibilities (2022) is thus a state of affairs and a portable laboratory. By gathering together under a glass case a series of attempts to reproduce the world on metal plates, paper and stone, the artist creates a sculpture that presents the different forms that photography could have taken. “By exploring the ancient processes of photography, I discover what photography could have been, that is to say, possible scenarios that have not been exploited,” she explains.

By envisaging futures that have not happened, Hanako Murakami turns research into poetry. Studying the "premises of the beginning", as she likes to say, she creates a resolutely contemporary work that questions the conditions defined two centuries ago to satisfy our desire to see the world. Similar to an archaeology, Hanako Murakami's undertakings akin to Michel Foucault’s project. "It is something like this that Michel Foucault must have had in mind when he wrote that his historical investigations of the past were only the shadow of his theoretical interrogation of the present," wrote the philosopher Giorgio Agamben in What is the Contemporary? (2007). Hanako Murakami's work is both resistance and consciousness.

— Jean-Kenta Gauthier, October 2022